…

…

Real-life counterparts of conceptions of things to come can appear in unlikely places, including some in the past.

But, you may say — surely not the online Daily Mail coupled to the Chinese user-videos-plus-shopping platform, TikTok? Yes, and yes. But also from, of all people, the supreme William Shakespeare — or what literary experts and historians searching for the indisputable facts about his life have unearthed in recent decades.

This improbable group answers the question of what evidence there is for the practicality of a keiretsu-cooperative to succeed the noxious advertising and personal data collection-dependent surveillance business model for journalism and publishing.

Though legacy media’s need for an innovative financing scheme and structure has proceeded from dire to desperate, this has somehow gone unmentioned in 2024’s mournful stream of reports about the decimation of employment in the news business.

In noting that over five hundred jobs in U.S. print, broadcast and digital media fell to cost-cutters’ axes in January, Politico said that this followed layoffs of 3,087 in the same categories in 2023 and 2020’s high watermark of 16,060. A 5 March reminder in the Financial Times of 450 journalists losing their jobs in Britain’s dominant Reach publishing conglomerate last year — because of an advertising slump linked to a steep slide in its newspapers’ online reader numbers — was not accompanied by any discussion or speculation about ways to stop or reverse the trend. Legacy publishers exhibit no outward signs of interest in remedies except for tried and tired variations of subscription terms or experiments in taking paywalls up or down to limit what visitors to their sites can read.

The New Year’s Day post here drew attention to the lone, faint glimmer in this doom-saturated panorama: old media managers do at last understand that reader-commenters are poised to become the core of their economic survival plans — the same people at the heart of the keiretsu-cooperative.

These are the visitors — effectively, informal, indie micro-publishers — luring and engaging site traffic who in 2010 were still commonly referred to as ‘bloggers’. January’s p-G jottings about them recorded that the business brains at some newspapers have begun to treat reader-commenters’ reactions and other ‘content’ like gold dust. As a result, some of them have begun — shamefully — to slap copyright claims with no legal justification onto those contributions from audience members, including many who are handing over cash as site subscribers.

How long is it going to take before most of them understand all the transformations underway sufficiently to see that reader-commenters are well on their way to morphing into:

— CONVERSATION PARTNERS ON EQUAL TERMS

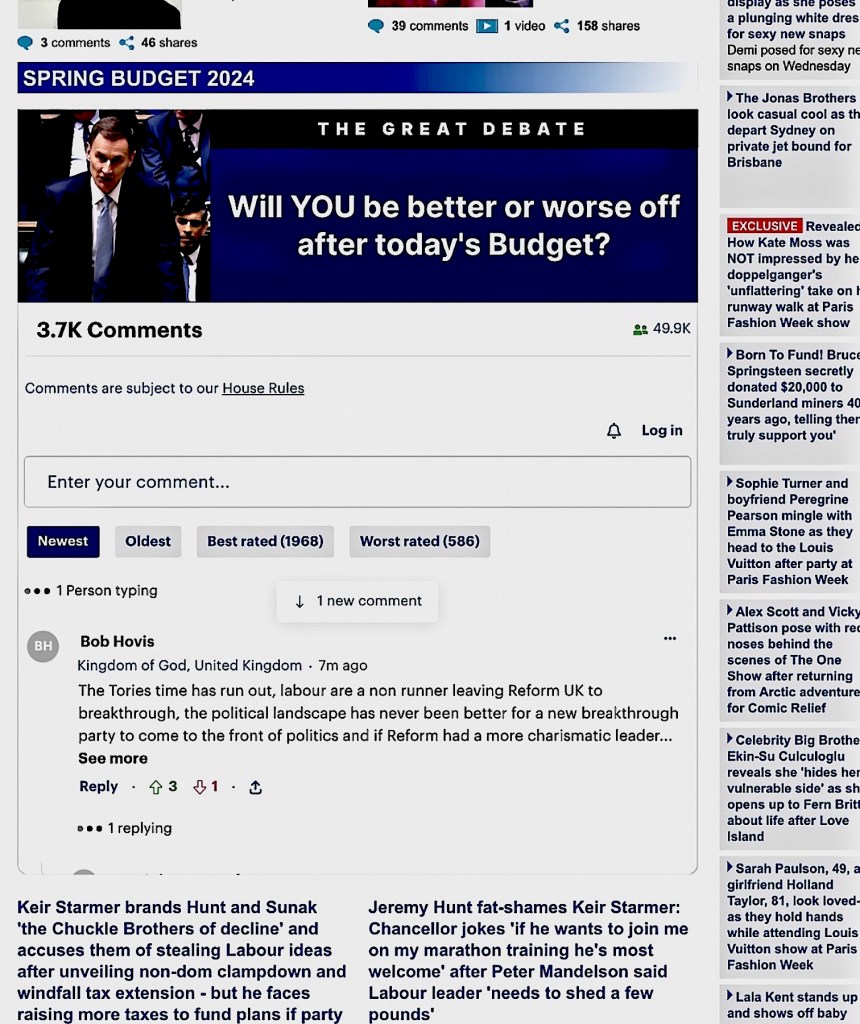

or ‘interactive’ audiences who are no longer mere receivers for broadcasts by newspaper reporters and opinion writers. On 6 March, anyone popping in at the online Daily Mail would have noticed an apparent experiment — placing at the centre of its home page a blank commenting box inviting readers to have their say on the U.K. government’s spring taxation and budget announcement.

This invitation was set in a screen within a screen with a moving scroll of other readers’ thoughts on the topic (see screenshot above, taken when the comment count had reached 3,700).

The overall impression was of a live demo of William Dutton’s portrayals in The Fifth Estate (2023) of ‘networked individuals’ becoming powerful as ‘a new source of accountability, not only in government and politics but also in all sectors of society.’

— CO-PERFORMERS

The online Daily Mail is the world’s fifth most-popular English language news title. It also magnetises more visitors to TikTok than any other purveyor of news on this Chinese-owned (ByteDance) social media platform where anyone can upload short videos they have made; earn cash from advertisers through product placements and promotions if they can lure enough traffic; and buy things hawked to them.

Publishing for people catching up on news where they go for relief from boredom, to play amateur auteur or entrepreneur, or to risk becoming shopaholics looks unavoidably like the future of journalism — because these people are disproportionately the youngest adults.

In a mid-January feather-fluffing announcement, the Daily Mail Online claimed to have ‘surpassed 10 million followers’ on TikTok (estimated by backlinko.com, to have soared beyond X-Twitter, Telegram, Reddit, Pinterest and Snapchat in platform popularity measured by ‘monthly active users.’)

The paper summed up its TikTok triumph as icing on the cake for its ‘unrivalled position as no.1 for engagement with audiences across all platforms.’ It explained that ‘[a]ccording to research by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 20 per cent of 18-24s use TikTok to learn about current events, which was an increase of five percentage points from the previous year.’ A follow-up story in February quoted other research ‘showing that more than 40 per cent of 18-24s receive news from the Chinese-owned social media giant once or more times a day, compared with 19 per cent for the BBC, Instagram (44 per cent), Facebook (33 per cent) and Elon Musk‘s X (24 per cent), formerly known as Twitter.’

Luck being what luck is, my 2010 outline of a scheme for post-Gutenberg publishing, six years before the birth of TikTok, began:

New communication technologies have created a karaoke world. It is not just that we have the means to ensure, cheaply and easily, that—as Andy Warhol predicted— everyone could be world-famous for fifteen minutes … Practically nobody is content any more to be just a spectator, reader, passive listener or viewer. Audience participation as well as the right to talk back—which includes non-expert reviewing of works or performances by trained and seasoned professionals—have become absolutely standard expectations.

— STAKEHOLDERS AND CO-DETERMINISTS

Few card-carrying cultural elitists inclined to shrug loftily about TikTokers earning cash from homespun, unmediated webcasting — making them de facto stakeholders in the platform’s success — will know that without the democratisation of culture in his own revolutionary epoch, we would never have heard of William Shakespeare. That man of mystery incommensurably more gifted than any other literary genius — forget TikTokers — has emerged from recent literary and historical sleuthing not as the aristocrat lurking behind a pseudonym in the centuries-old rumour, but incontestably a ‘country boy.’

He was ‘the grandson of a yeoman farmer and the son of a failed provincial shopkeeper,’ in his portrait by today’s pre-eminent Shakespearean scholar, Jonathan Bate, in Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare (2009). He got his start in playwriting by polishing the scripts of other writers while enduring mockery as ‘an upstart crow,’ a ‘rude groom,’ and a ‘peasant.’

But this book’s most unexpected revelation, for many, will be about Shakespeare’s business acumen, an asset as rare in writers then as it is now. He died a prosperous landowner at fifty-two, leaving his wife and the children he had fathered before his twenty-first birthday well provided for from his earnings as a shareholder in an acting company that operated very like a cross between an artists’ collective and a cooperative venture in our time.

Through becoming a shareholder, Shakespeare was the first to turn play-making into a potentially rewarding profession that could support a marriage and a family. His fortune was made not by a literary innovation but by a business decision. In his early career, Shakespeare would have noted the raw deal suffered by the script writers, who were paid only a few pounds per play. The serious money was made by manager Henslowe and lead actor Alleyn, who ran the Rose Theatre as an entrepreneurial partnership. Shakespeare and his close associates came up with an alternative arrangement: the Lord Chamberlain’s Men was formed in 1594 as a joint-stock company, with the profits shared among the players.

…

What could have been the equivalent of reader-commenter power for Shakespearean audiences?

The 20th-century historian John Hale has shown that unlike the ‘patron-fostered painters of Italy, the Low Countries and Germany,’ the Bard ‘was reliant on popular support, as were his fellow playwrights.’ Their works and the venues for their performances were part of a democratically inclined ‘theatrical machinery that both responded to and increased the number of spectators and dramatists.’ Another impression from reading The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance is of how uncannily today’s social media frenzy resembles the explosion in early 17th-century mass entertainment in London:

During the boom period of new plays, 1600-10 … the places available each year in the commercial theatre, discounting Sundays and Lent, may have topped a staggering two million when the population of London was two hundred and fifty thousand. Never before in Europe had there been so heavy a vote of confidence in a single form of cultural activity.

In another prefiguring of the present, Civilization shows the joys of expanding free expression for playwrights soon proving to be too much for the authorities:

Altogether the appetite for theatrical dialogue and effects was so constant as to enable a playwright to indulge his own aspirations short of flagrantly inviting political and religious censorship; bawdiness was let slip with a shrug, a contributory reason for the Puritan criticism which led eventually, in 1642, to the order that the theatres should be closed altogether, an order honoured almost as much in the breach as in the observance.

Some of the Puritans especially disgusted by their inability to control this tide in public affairs presumably let a different one carry them away to found a new colony on the other side of the sea. But here we are now, being reminded that the most satisfying narrative arcs can turn out to be circles.

The keiretsu-cooperative seems to rhyme naturally with what has gone before, not just with what will or should be.