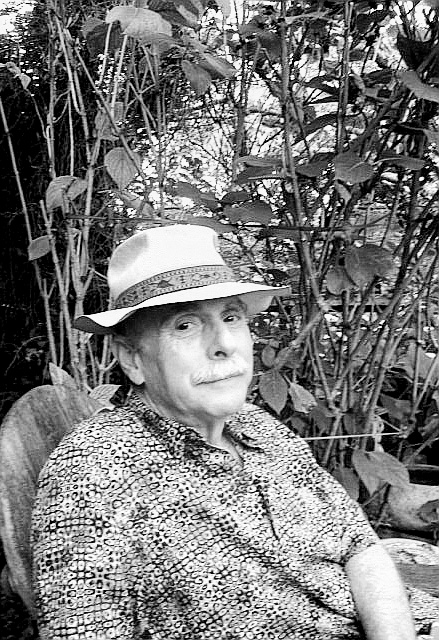

Howard Rheingold, the ‘smart mob’ and ‘virtual community’ man, hardly needs a gatekeeper

Conventional publishers do not know enough to act as omniscient filters for manuscripts. The 70 per cent royalty Amazon.com is paying to indie writers publishing their own e-books brings hope of fair compensation — at last — for the struggles of brilliant authors like Howard Rheingold.

Prescience and vision are not easily transmitted between minds – any more than an ear for music is, or a gifted wine-taster’s palate. This makes the tradition of gatekeepers deciding which texts are published absurd, and increasingly so. Once, big publishers and book agents were often literature-loving animals with weaker or stronger business instincts. Now, they are almost exclusively – proudly – spread sheet-driven beasts. The most successful of them, in their terms, are pragmatists too narrowly educated to know or care about ideas. It is hardly surprising that they are incapable of vetting them for either soundness or significance.

Consider Howard Rheingold and his thoughts about the technological future. He foresaw the lightning coordination – owed to what a time traveller from the ‘70s would perceive as plastic matchboxes – of the protests in the Arab spring, and the British riots. His term for the phenomenon has its own entry in the Wikipedia. It was the title for the book he published about it in 2002: Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution.

In recent weeks, Howard has been putting the finishing touches to Net Smart – his book about ‘everything you need to know to thrive on the internet’ – downloadable to e-book readers next spring. I expect him to have a lot to tell us that we do not already know, as he has a startling record for accurate guessing about how technology is about to transform our lives, yet again. He predicted, for instance, the online fellowship we are nearly all part of, now, in his 1993 book, The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier (downloadable here, on one of his sites, for payment by the honour system.)

The famous names in trade publishing dithered about how much support they were willing to commit to the writing of Net Smart, in spite of the monumental proof of Howard’s wizardly foresight.

‘I’m five, ten, years ahead of what they can see or understand,’ he mumbled in an embarrassed aside, when I joined him on his hour-long daily constitutional last week. He flapped an exasperated hand in the air as he said that, marching at a cracking pace around a tree stump, and through California coastal scrub and brush near his house in the peaceful, ex-hippie town of Mill Valley, where Jack Kerouac once perched for a while.

Instead of a mainstream publisher, for a book about technological survival for us ordinary people, Howard is working with the MIT Press – associated with the great Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I have been considering, for a parallel, an author with a string of successful books anticipating how aeroplanes would globalise food, clothes and the sexual revolution, who must now rely, for a green light, on a gatekeeper specialised in vetting texts on aeronautical engineering. This seems ridiculous, even if the gatekeeper — in this case — enjoys prestigious straying outside strict academic bounds.

Who do I think Net Smart’s publisher ought to be? Howard himself.

Yesterday, there was yet another sign that indie publishing in taking off at top speed. In New York, the Perseus Books Group launched a distribution and marketing arm for authors publishing their own books – following Amazon.com (in which I am a sub-microscopic shareholder) in giving authors of e-books who use the service a royalty rate of 70 per cent, as opposed to the traditional 10-15 per cent that has long been standard in print publishing. This percentage is a more honest reflection of what publishers have been doing for most authors for decades, except that it is hard to believe that Perseus will actually do much marketing for any author not writing reliable best-sellers. Publishers have long expected writers to do nearly all the marketing themselves.

Certainly for writers angry about the unfairness of the usual split between author and publisher, this alteration is at least as important as the French Revolution. Better, in fact, since it has no disagreeable spectacles involving people-butchers lopping off aristocratic heads as crowds cheer madly.

Howard said that he was strongly tempted to go indie with this book, but decided that he wanted a traditional book advance one last time. I met him in the mid-1980s, when a mutual friend sent me to him for advice about whether I could survive as a writer outside captivity – leaving the large magazine that employed me. He could not have been more encouraging, but warned me that to pay the bills for the most simple life, I would have to work around the clock as he did, with almost no play time, not even at weekends. His wife Judy nodded in confirmation (gosh, were they right.) She, too, was working punishing long days, cutting and styling hair, proving her faith in his vocation.

Why must Howard, who has always understood the importance of both his own best perceptions and those of many a scientist and academic working in obscurity – and made an ever-wider market for them – continue to give away most of the revenue from his books to mere text-packagers?

He is and has always been too busy to rail against injustice. While he waits for Net Smart’s debut, he is supplementing his income from writing with exhausting expeditions to lecture at Berkeley and Stanford, as he had done for years. One of his projects involves pioneering the ‘co-teaching’ – through collaboration with his students — of online journalism, and the effective use of social media. On Twitter last month, he was advertising his new, all-online university, Rheingold U, specialising in ‘the literacy of cooperation’:

The term “collective action” may be dry, but the mysterious magic that enabled homo sapiens to use symbols to organize group activities like hunting or agriculture is what distinguished our ancestors from the other scrawny primates on the savannah […] Although this might seem far removed from the questions posed by digital networks, our species might be in for another leap into an entirely different level of complexity and way of life, depending on how we use digital networks to collaborate in new ways and on new levels.

When I have read Net Smart in a few months, I shall have a bit more to say about Howard – and hope that he will, by then, have made the leap into the next, entirely different phase in the evolution of publishing.