Dear Reader, our wish for a Happy New Year comes in the spirit of the lovebird mentioned here, in this set of advance instructions:

When a baby budgerigar died in a cage adjacent to the lovebird’s the latter grieved horribly for three days. She sat on her perch with her eyes squeezed tightly shut and ignored all attempts to communicate with her. She ate meagrely — but after three days, she put the matter firmly behind her and would entertain no reminders. She had returned to her usual vivacious self. So there you are, the animals are ahead of us. Humans are always uncertain about the policy in any situation, but animals …possess an answer to all problems.

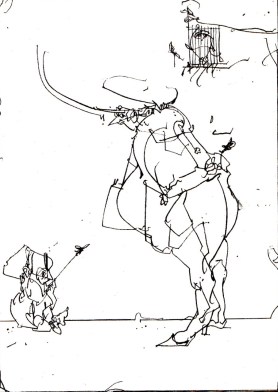

The witty, magisterial line of Sascha Juritz, about whom we posted earlier this year, accompanies those thoughts of ACB’s, an ardent admirer of feathered creatures, whose flashing communication about an iris we recently recorded in this spot.

What came to mind when we revisited Sascha’s sketch yesterday was the title of a short story, ‘The Old Chevalier,’ from the Seven Gothic Tales of Isak Dinesen, to whose incomparable oeuvre post-Gutenberg was introduced by that same ACB — one of the two most significant forces in our existence — to whom we had no choice but to say a final good-bye last week.

Reflecting on her life, we find ourselves thinking often about Dinesen’s ideas about redemption through literature and art for all those who feel more thwarted than not; who can justify seeing themselves as victims of implacable, virtually lifelong, opposition to their hopes, dreams and plans.

Our woolgathering inevitably led us to Google, where we found, first, an appreciation by Susan Hardy Aiken of the most famous Dinesen story, ‘Babette’s Feast,’ whose theme the critic considers a reprise of another tale by the same genius, ‘The Supper at Elsinore’ — ‘a story of failed flight, of “all the betrayed and broken hearts of the world, all the sufferings of weak and dumb creatures, all injustice and despair on earth” …’ …

Of the later story, Aiken tells us:

… [T]he haunting presence … is … a revolutionary woman. At once ‘beggar’ and ‘conqueror’, benignly maternal and bewitchingly seductive, a festive, unclessifiable figure who makes ‘righteousness and bliss kiss one another’, Babette is also … a ‘great artist’ with ‘the gift of tongues’ whose concoctions can transcend and transform the confinements of culture and the misdirections of history. … Writing ‘Babette’s Feast’ in her old age, at a time when her own body was consumed by incurable illness, Dinesen would enact her artistic transcendence of that carnal confinement, offering her readers a ‘celestial’ feast of words, a ‘blissful’ feminine Eucharist able to redeem those who are failed or thwarted …

Then we found, in Susan Brantly’s book about Dinesen, a reminder of the reason why this author was first published outside her Danish homeland:

Dinesen’s reception in the United States was enthusiastic beyond all expectation [ … but her… ] misgivings about how the Danish audience would receive her book proved to be well founded … [Her] imaginative tales set in the previous century were quite different from what most Danes were reading. Svend Borberg described Dinesen as a flamingo-red orchid in a cabbage patch … The most notorious of the Danish reviews accused Dinesen of ‘snobbism, the fantastic, and perversity.’ The negative Danish reviews upset Dinesen. Svend Borberg, with a good dose of irony, suggested one reason for Dinesen’s being subjected to such a beating by the Danish critics: ‘It was naturally very cheeky, not to say brash, of Isak Dinesen — alias Baroness Karen Blixen — to conquer the world first with her book Seven Gothic Tales and then come to Denmark with it. As a Danish author she should have felt obligated to ask here at home first if she was worth anything.’

Ah, gatekeepers … We have posted about these beings before, when we considered Samuel Beckett’s opinions of them in a post here last winter. No doubt we will revisit the subject in 2013, if we can keep this blog going.