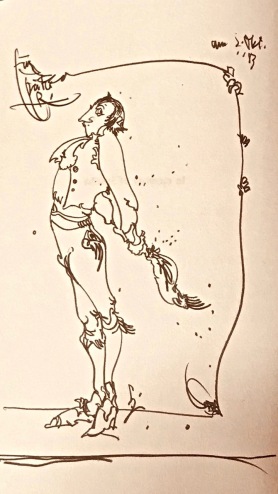

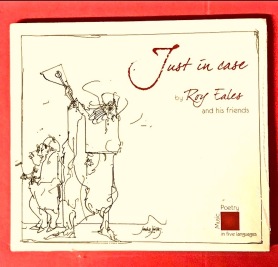

Portrait (above, from A poem decides) and cover art (below) are by Sascha Juritz, a lover of Breton culture who ‘saw Brittany as a twin for Lausitz, his own Slav country locked into the Czech and Polish borders’

…

Imagine the happiness of sitting on a sun-dappled terrace in the French countryside, where you have had to reassure, say, the oldest person at your café table — your dear, monolingual English father-in-law — that you suggesting that he try la tarte du village has nothing to do with the two ladies of the night before, loitering beside the picturesque stone bridge in décolletage more evident than clothes.

Forever after, this will be the most risqué story you will repeat and embellish at family gatherings, but — still in the original moment — everyone at your table goes on to order a second cup of coffee and sipping quantities of gullet-scorching marc. Why? To stretch out the pleasure of listening to the unannounced, spontaneous concert-with-poetry that has begun unobtrusively at the other end of the patio, a performance mostly in the language or dialect of this part of France that lets you crawl under the skin of the place, into the preoccupations of its people, as you could not hope to do on the usual sightseeing-and-feeding tourist rounds. Perhaps you strike up a conversation with the born-and-bred-here family at the next table, when they explain the history behind the lines of one of the songs you’ve been listening to, which reminds you of a novel by Stendhal or Colette you read and wept over as a teenager. Your satisfaction, your feeling of enrichment, becomes incalculable.

Unless and until most Europeans have sensory treasures like these to savour, personal experiences of being in other EU nations, the Unión Europea, Europäische Union, Unione Europea and so on … will never be more than a merely pragmatic head-over-heart construction. This autumn’s dismal Brexit negotiations resemble the arguments in a divorce battle at the end of a marriage notable not just for a lack of love or passion but simple affection. It is a union of countries joined in the equivalent of an arranged marriage that made unassailable good sense on paper — but in which the parties never made any effort to get to know each other at the level of scent or touch, let alone become mutually endearing; or develop shared habits; or accumulate a store of common memories.

And how can you tell what a true inter-cultural marriage — respecting and revelling in cultural differences — would be like?

There is a sort of — marvellous — answer in a set of performances captured on Just in Case, a CD first mentioned on this site six years ago that reappeared in a bookshelf-tidying exercise the other day. It sounds sung and spoken straight from the souls of Bretons about scenes and old legends of Brittany, although all its material is new, and it lets you hear Breton voices — including one that is especially gravelly and magnificent, belonging to Fañch Peru, to which you can listen on a clip uploaded here — singing or reciting poetry, some of it protesting, conveying the depths of understandable anger about attempts by authorities in Paris to stamp out the Breton language as if it were a foul pest.

But no, not all the performers are actually natives of Brittany. Among them are Marianna Butenschön from Germany, Owen Martell and Tomos Williams from Wales, and several from other French regions.** All the poetry and lyrics are by Roy Eales, a part-time inhabitant of Breton country whose forte is elegantly delectable whimsy with powerful undercurrents, and whose first language is English — even if, when reading English and French versions of his poems side-by-side, you might strongly suspect that several came to him first en français. The foreigners share Breton sentiments — cultural pride, outrage about subjugation — to a degree that would be implausible to anyone who had no idea of how many antifascist outsiders lost their lives fighting in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-9, including 500 from Britain and 900 Americans.***

Roy and his wife and perfect mate, the painter Susan Eales, have with a fine and cherishing ear translated into English dozens of poems by a munificently gifted Flemish friend of theirs, Willem Roggeman, published in A splendid view on words. He has reciprocated, introducing Flemish readers to Roy’s poems in his own English-to-Flemish renderings.

Like Just in Case, none of these collaborations and exchanges were subsidised by the EU or any government, as far as we know, or organised by official edict, or prompted by worthy kumbaya ambitions.**** They seem to have come about from natural attraction, or what is most essential in art.

If only they were more common, and were advertised and shared more energetically — not necessarily on the internet, where you can find uploads of the odd clip from Just in Case that, certainly at this stage of technological evolution, sound woefully anaemic and fail to do justice to its impeccable, professional production.

The collection’s tone is set by Julie Murphy, born English, but singing translations of Ealesian verse into Welsh — the language of her husband’s people — in a warm yet sublimely ethereal voice, as movingly as the young Joan Baez (and yes, that is saying a lot). It is a performance with an intimacy that cannot be faked, free of the annoyingly over-the-top emoting of too much Celtic fusion music, and of slick, big-studio tricks and manipulation. You, the audience, seem to be a privileged eavesdropper, as when listening to the riffs of jazz musicians who have been playing together for an eternity, or the improvisations of a classical Indian sitar-and-sarod ensemble — even if the pieces that make up Just in Case are not live recordings.

Saying more than this would approach literary or musical criticism. At post-Gutenberg, we prefer to let work speak for itself, on the whole — a preference that the objets d’art in this poem would certainly share:

Royal Academy of Arts

…

Nobody asks

how the paintings feel

when the exhibition is over.

Is it not then

that these tired oils

deserve a little rest?

They have seen enough

eyes and heard enough

words of artful observers.

Enlarged by a superior sense

who speak aloud, these masters …

… these accountants of

image, of culture,

these over-filled vessels of real meaning

(they speak of this work or

that to anyone

who listens till nobody hears).

These onlookers

must be taken down.

The paintings decide they can’t take any more.

…

— Roy Eales, in A poem decides/ Ar barzhoneg an fini a ziviz/ C’est le poème qui decide/ Ein Gedicht entscheidet (2013)

…

…

** Reciting the names of the musicians and performers makes a feast for the ears — or aural overload. A by no means complete list would also include: Bernez Tangi, Marthe Vassallo, Emmanuelle Huteau, Nanda Troadeg, Kemo and Matilda Veillon, Jean-Michel Veillon, Yannick Jory, Jean-Luc Thomas, Pierrick Tardivel, Philippe Gloaguen, Philippe Ollivier … And then there are the translators from English: Fañch Peru (Breton); Nanda Troadeg, Marie-Noëlle Le Tallec, and André LeFèvre, in addition to Roy and Susan Eales (French); Maria Tritschler, Marianna and Wolf Buenschön (German); and Owen Martell (Welsh). For your own copy of the CD, telephone or write to Marie-Pierre Le Pennec, Le Bourg, 22140, Pluzunet, France. Tel: mobile -0033635911833. €16.50 (including p&p). Email: marie-bzh-22@orange.fr

*** In the first part of her autobiography, An Unfinished Woman (1969), the playwright Lillian Hellman — who travelled to Spain to report on this war — wrote: ‘Never before and never since in my lifetime were liberals, radicals, intellectuals and the educated middle class to come together in single, forceful alliance.’

**** A kind note from Roy on 23 September added valuable enlightenment, summarised as follows:

The artists worked together for four years without any external financial support. Once the collection of performances that became Just in Case was ready in final form, funding for production of the CD and for concerts to promote it arrived from: the cultural services section of the Conseil Générale of the Côtes-D’Armor and Itinéraires BIS des Côtes-d’Armor (the département where the Eales family and Breton and other artists have homes); Stiftung Brass, a cultural foundation in the German city of Aschaffenburg (which had in the past supported and helped to arrange exhibitions of the works of Sascha Juritz, see above); the Arts Council of Wales and Welsh Arts International; and Dao d’a r C’had and Ti ar Vro, two Breton cultural associations in Cavan and Pluzunet. After Just in Case was released, France 3 Television chose it as one of the three best CDs of 2011.