photograph in honour of the Chinese Year of the Snake: http://www.sheffieldkungfu.com

Abdication of responsibility is a serious charge.

Even as we type, we are close to fainting from disbelief that The Economist and The New York Times deem the deliberations about press reform in a leading democracy – negotiations in which a prime minister is directly engaged – unworthy of either reportage or commentary. Neither of these leaders in print journalism has run a single piece about the Leveson Inquiry since they recorded the publication of its report. Unless Google is mistaken, the scintillating newspaper in St. James’s last pronounced on the subject on 8 December; the grey lady, proud of treating the world as its oyster on other subjects, on 5 December.

For reasons explained here in two earlier posts – passing on advice from the Chinese sage Lao Tse, and pointing to the pointlessness of making new rules for a dying institution – post-Gutenberg sees press regulation as wasted effort. But over 75 per cent of the British public does seem to want the recommendations of the Leveson report put into practice. Surely this, and the haggling over Leveson’s conclusions by the British government, politicians and media, merit analysis and debate?

Skilled and eminent doctors have to treat and be treated by other doctors, when they fall ill. Judges are not above the law; lawyers must be prosecuted and defended by other lawyers. The equivalent, for the press, of ‘Physician, heal thyself,’ has to be ‘Journalist, your work is not above dissection and condemnation by colleagues, without fear or favour.’

We once admired the NYT’s media columnist David Carr for his apparent fearlessness and perspective (see ‘Why not occupy newsrooms?’ 23 October 2011). For over a year, most of his columns have left us wondering just who tied and gagged him. Yet none of his timid recent work has been as alarming as his bizarre focus yesterday on the lengths to which an energetic Midwestern newspaper columnist went to trace the hands that took a photograph of an exploding manhole cover in Omaha. That’s right — not a column about, say, media coverage of the responsibility for the explosion; just a mildly entertaining ramble about the origin of the image. There have been reports over the years of infinitely more ingenious sleuthing that has, for instance, united the finder of a camera lost in one country with an owner thousands of miles away in another – by altruistic amateur detective work by strangers that entailed uploading pictures from the device to the net and posting requests for help on social media.

As for Carr’s subject, surely it was the photographer with the fast reflexes of a citizen-journalist who deserved his praise, and not ‘[gums]hoe leather’ that, according to this NYT columnist, ‘never looked or smelled so good.’ The reader is left baffled by his conclusion: ‘And it’s a useful reminder that even though daily newspapers are a threatened species, they continue to have value in the informational narrative.’ Phew.

More to the point, what is Carr doing, writing about manholes but not ♯Leveson – a subject of keen interest to the planet, judging by the attention the Inquiry has been getting on every continent? (as search engine analysis of traffic brought to this blog, for one, confirms). Was his upgrading of an amusing dinner table anecdote to the focus of a whole media column actually an encoded scream for help – a demonstration of the humble scraps that a good reporter like him is obliged to offer his readers because barred by someone (precisely who?) from doing his job?

If the NYT did not anticipate reactions exactly like ours to its media columnist’s disappearance down a manhole – façon de parler — why is the column closed to comments? (or certainly was, when we last checked a few hours ago?)

But as for the infinitely more critical cause for anxiety, what vital information is that newspaper, like The Economist, failing to give audiences?

Go to the website of the International Forum for Responsible Media (INFORRM) – run by lawyers – and look up:

‘Hacked Off responds to the draft Royal Charter: “a surrender to press pressure”’, 12 February 2013

… and …

‘Leveson: It is impossible to overstate the Daily Mail’s fear of proper press regulation’, 17 February 2013

You will be afraid, very afraid, when you read what highly regarded publications do not want you to see — and of what there would be no record of at all, without blogs like INFORRM’s.

… Only psychologists, Chinese mystics and lovers of poetry will want to know that as post-Gutenberg awoke last Sunday, the exquisite final lines of a D. H. Lawrence poem came floating to mind, out of the blue, on an unexpected wave of the sort of happiness with which we witness beauty:

And I have something to expiate:

A pettiness.

They belong to ‘Snake,’ poetry at its greatest, for more reasons than we have time to suggest. As we puzzled over the mysterious reminder of them, fingers tapping into a search engine box, we found that the poem had been the subject of a lovely meditation by Jacques Derrida.

The ‘I’ in the poem is overwhelmed by admiration for the way the reptile looks and moves, but, obeying ‘the voices of my accursed human education,’ throws a stone at it – and

… suddenly that part of him that was left behind convulsed in undignified haste.

Writhed like lightning, and was gone

Into the black hole, the earth-lipped fissure in the wall-front,

At which, in the intense still noon, I stared with fascination.

And immediately I regretted it.

[…]

And I thought of the albatross

And I wished he would come back, my snake.

[…]

And so, I missed my chance with one of the lords

Of life …

… About which Derrida proposes, with Gallic convolution, that

‘It is indeed on the side of chance … and toward the incalculability of another thought of life, of what is living in life, that I would like to venture under the old and yet still completely new and perhaps unthought name democracy.’ [his emphasis]

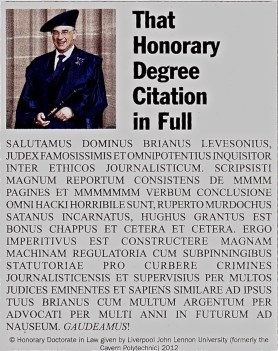

The Chinese Year of the Snake began either on the 4th or 10th of this month, depending on which authority you consult. Did the dream-like entrance of the ‘Snake’ lines have more to do with the private or public sphere? Was it something like a parental warning not to descend to the pettiness of a particular someone whose physical bulk is in direct, inverse proportion to a tendency to small-mindedness and jealousy? In the wider realm, a snake might easily be symbolic of all the forms of competition from citizen-journalists and bloggers so hated and feared by the old press establishment – unwelcome power-sharing.

Yes, democracy.

And that is as far as we will get with de-mystification – for the present.