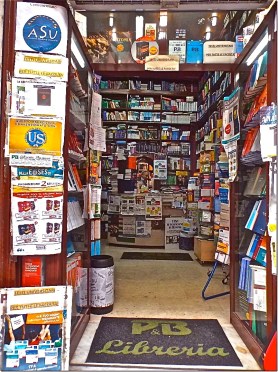

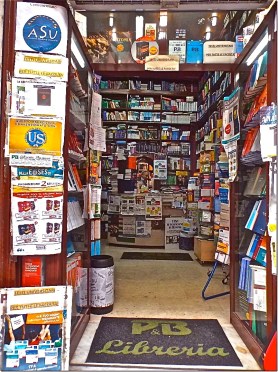

Will the flexible, accommodating online counterpart of the ‘libreria’ or bookshop everywhere supplant the change-resistant ‘biblioteca’ — Italian for library – in the digital revolution?

– photograph from Napoli: MIL22

…

This entry tells a true story of our time about a public library that recently turned down a modest proposal for listing on its web site books published independently by its patrons and members. Note that there was no request to include these – necessarily – in the library’s catalogue. The frame for our tale is an open letter about an exciting vision for libraries of the future by an inventive leading librarian.

…

Dear David Lankes,

Dear David Lankes,

Can public libraries supercharge the flowering of indie publishing and go back to being vibrant centres of creativity?

I have been reading your slender Expect More – a book I will call thrilling. As you know, that is not a word that I or anyone else thinks of, any more, in connection with libraries. Least of all, those of us who saw them as unrivalled homes of enchantment, growing up; entertainers for which no television set, nor the most luxurious cinema with the biggest screen was any match. Part of what you have set out so well is that if the visions of a true 21st-century librarian can be realised — in, around and beyond the stacks — libraries could return to their glory days, in ancient times, going all the way back to the legendary 3rd-century BC Library of Alexandria.

I note that you are a professor of library science in Syracuse, in New York state, and a leader in information studies exploring ‘how participatory concepts can reshape libraries and credibility’. You say:

Too many librarians see their collections, not the community, as their jobs. Too many librarians are seeking to survive instead of innovate, … [… ] Great libraries … require open communication about your needs, your challenges, and your dreams. […] Libraries ‘for the people’ is an old way of looking at libraries. The new view is the library ‘of the people.’

When a library director has to be replaced, does the typical library board – or electorate, when the vetting is democratic – know what to look for, to choose the right leader for our times? That would be someone like you or Phil Shapiro, whom I’ve seen described as an educator at a public library near Washington D.C., who ‘teaches an occasional graduate educational technology class at American University’. His @philshapiro notices on the Twitter bulletin-board are quirky, sometimes impish, and essential reading, and led me to you and your book. In a 2008 entry on his ‘Community Voices’ blog on PC World’s site — ‘Should Public Libraries be Welcoming Homes for Ingenuity?’ — a biographical note explained:

In high school he built a hot water solar collector from an abandoned shopping cart and hauled it up onto the roof of his house with a rope. His parents thought that was a good idea. The neighbors were not entirely thrilled with the shopping cart. On the roof. Of the house.

That suggests that the questions people selecting library chiefs should be asking in job interviews or library-related elections are, ‘How young were you when — if — you appalled people by doing things that later confirmed you as one of the pioneers in your circle, and can you give us some examples?’

In my life divided between several perches, in recent years, experiences at public libraries amply bear out your characterisation of too many people working in them as ‘stuck in a sort of professional conservatism that favours what they do over why they do it.’

Not long ago, I asked one head librarian whether our library might support the indie e-book revolution by encouraging patrons to list on the library web site the titles of any independently published books for which they were responsible. I said that I envisaged a bare-bones listing of each book’s title and subject – with, perhaps, a link to the author’s personal web site. This stark recording, I thought, would discourage competitive promotional hype and one-upmanship. The idea for the list had occurred to me when I realised that a number of potential readers of my first e-publishing experiment — a short book (or long essay), Jung on men and women: a Swiss travelogue — happen to live in this particular library’s catchment zone. It is not unusual to meet local residents who are widely travelled, devour travel literature, and are interested in psychology, Switzerland, the fight for women’s rights, and the theories of Freudian psychology’s chief 20th-century rival, Carl Jung.

It seemed to me that libraries might be able to link local readers to writers in ways that the algorithms of Google and Amazon cannot. I would love to glean, from a constantly updated record of books they were publishing, impressions of the obsessions, preoccupations, passions and undisguised money-making schemes of people who live nearby. Living in the same place can mean much more than a shared or neighbouring postal code. Among those of us situated where we are from choice, not just necessity, it seemed as if there could be indefinable but powerful resonances predisposing us to being interested in each other’s literary and graphic creations. Whether I was right or wrong in this assumption, it seemed worth a test.

The head librarian — someone said to be charming whom I have never met in person — replied both directly and through a mutual friend. The idea, I gathered, was a non-starter. The staff already had too much to do without making and updating my proposed list. Though the library is neither a valiant inner-city nor struggling rural branch but located in a large, rich suburb, there were no funds for hiring new workers. What about letting volunteers – patrons – do the job? No, that was out of the question. Why? Because the library chief had tried working with local volunteers and quickly been worn out by the complications of being assisted by those most in need of occupation, bossy ladies-who-lunch types, many of them strangers to workplace discipline. In addition, an overbearing patron who had just published a book for teenagers had been hounding library staff members for help with publicity.

I was sympathetic to these reasons for the proposal’s nervous reception. Well then, I suggested, how about making a specific request for help from seasoned professionals in the ranks of the town’s retirees? What about letting retired administrators or book-keepers, doctors, teachers, company managers, accountants, lawyers and so on, get involved? But I made this counter-suggestion hesitantly, in fading tones, accurately anticipating defeat – because I had by then detected a faint but unmistakable whiff of hostility in a reference in one email from the librarian’s intimate friend to ‘this promotional idea’. I had been careful to explain that the list of e-books published by locals that I envisaged was plain enough to be the antithesis of anything sales-y. To no avail, apparently.

Prejudice can get in the way of reading or hearing what someone has actually said. What would the prejudice be, in this case? At a guess – your characterisation of the typically change-resistant librarian’s view of the purpose of a library – ‘providing access to knowledge,’ where that is perceived as a ‘passive … accumulation of facts,’ and not, as you say it should be, ‘intimately tied to the passions of the individual … dynamic, ever changing and alive.’ Too many libraries, you add, ‘support consuming knowledge instead of creating it.’

Phil Shapiro, arguing along closely parallel lines in a post titled ‘Towards a National Transition Plan for Libraries,’ asks whether libraries should ever close their doors:

In an information-based economy where knowledge workers drive almost all innovation, shouldn’t the public knowledge place be open seven days a week? If 7-Eleven and FedEx Office and McDonald’s can stay open 24 hours a day, is it not possible for libraries to do so, too?

As it happens, a few days before I read that, I’d made the nearly identical point to the circulation staff of a library. I said that they were surely sealing their institution’s doom with rigid, daft rules and systems that make it look more out of touch with reality, every day, to patrons accustomed — for example — to being able to buy discounted books online at any time of day or night, and avail themselves of exceptionally elastic and forgiving returns policies to unload themselves of purchasing mistakes. Don’t libraries realise, I railed, that their worst policies are so despised by patrons that some of us have been whittling down our reasons for borrowing anything from them at all – and actively developing other routes to acquiring everything that they alone could once supply?

I’d been complaining bitterly about being obstructed from paying a late fee because it fell below the threshold for permitting a credit card transaction at the circulation desk – though, by some impenetrable logic, if I went home and logged into my library account from there, I would meet no obstacle to settling my bill with my plastic rectangle. When I actually attempted to do this a few hours later, there was a block on the account because … no, no, I’ll stop there: the reason is too petty, tediously complicated and batty to recount.

As for the good sense in Phil’s advice about adjusting to the information economy — well, a library worker in another branch for whom I have nothing but high praise once explained that the reason why the software download speed on his library’s network can slow to approximately zero megabits per second — even forty-five minutes before closing time — is that the staff do not want patrons getting in the way of closing time routines. They simply shut down internet access to encourage these patrons to leave. I asked how that was possible when the library’s wifi network is supposed to be on all day and night. ‘Right,’ he said. ‘So when you’ve all left, they turn it on again.’ This reminded me of a minder of the public internet-access section of a library, a woman I had never seen before, hovering nearby, tidying desks and watching me type my library card number into the login box at least nine times in a row, trying to get online — with no success. Only when asked for help did she explain that she had already tucked the wifi system into bed – fifteen minutes before the end of her work day.

So, David, imagine trying to make the mental transition from that — a set of far from uncommon reasons for contemporary libraries being a depressing subject of conversation — to your description of ancient Egypt’s fabled book-haven in Alexandria. A place that you say was ‘not a huge document warehouse’, but ‘much more akin to universities of today’, where ‘[s]cholars from the known world were brought together and encouraged to talk and create.’

The contrast is agonising and will get worse, unless you, Phil and other advocates for reform can find a way — fast — to add people like yourselves to the staff of public libraries in senior positions. My happiest discovery in your book is that my modest proposal for patrons letting each other know about their indie publishing projects is directly in line with the transformed library-land you perceive as essential:

In essence, too many libraries have defined access as providing access to their stuff. You must expect more from your library. You need to expect it to provide a platform where you can access the ideas of others, as well as a platform for you to provide others access to your own ideas.

I note, by the way, that you published Expect More yourself. I didn’t buy the e-book. I bought the attractive print-on-demand paperback, childishly delighted – as always – by the idea of a book printed specially for me.

Incidentally, I would love to know how you would have treated my suggestion for a continuously updated list of indie books published by members of a public library. If you ever see this post and feel moved to reply, I hope you will leave a comment here – or on some site of your own.

Best wishes,

CB

Dear David Lankes,

Dear David Lankes,![Cherish the old and get on with the new: the classic, by way of the digital photographs by EF and postgutenberg[at]gmail.com](https://post-gutenberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/basel-archtctre-museum-old-and-new-dsc00821.jpg?w=278&h=371)