John A. A. Logan poised to evoke the touch of evil in The Survival of Thomas Ford – and below, less alarmingly, with his mother, Agnes Logan

Photographs by Alasdair Allen (above) and northern-times.co.uk

…

‘We sly women are the world’s only hope,’ said Jan, ‘And not just any old sly women either. You can forget about yer Jews and Protestants for starters. And of course any woman who dabbles in atheism.’

‘You get them, man,’ said Bathsheba. ‘It happens.’

[…]

‘Still in deep denial about the Counter-Reformation, yer Prods.’ Bathsheba beeped the horn again. ‘The most comically perplexed souls of all time, poor things.’ Beebeep. ‘The ne plus ultra of human… Of human whit? Thingummibob. Whit’s the word? Cartoonishness? Am I toasty warm? Get us the thesaurus.’

Jan found it in the glove compartment and gave it over.

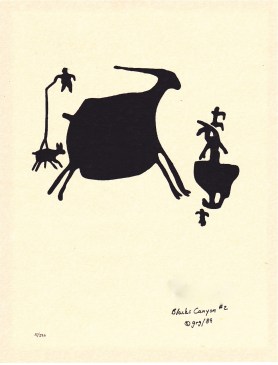

The Adorata, Sean Murray

…

What is the point of thrillers – the noir kind, especially?

Er, … entertainment, do you suppose? you suggest drily, stifling a sardonic ‘D’oh!’

To which post-Gutenberg’s answer would be, but what is the point of this sub-genre of entertainment?

Yes, yes … we know, an absurdly ambitious question for a funny little blog.

But this hardly rules out suggesting a line of enquiry for an answer: might the point of blood-and-gore electrified by crackling suspense be to fight horror with horror? That is, neutralise real-life horror, shock and sadness, with the imagined and invented kind? Nothing supplies temporary relief for the agony of witnessing the suffering of someone beloved in extremis – helpless to do much to relieve it – as well as a story so powerful that it takes control of your brain and entire nervous system, whether read in snatches or all the way through.

Events of recent weeks have shown us that a well-written thriller violent and gripping in direct proportion to the unbearable, in actual life, works better than any other literary form – particularly for a reader who loathes violent films and literature, and often resents the manipulations of narrative suspense.

The book is set aside, and the reader feels inexplicably stronger and ready to face down the monsters again. Some process less akin to catharsis than to Freud’s idea of displacement is surely at work – which, in a Wikipedia definition,

operates in the mind unconsciously and involves emotions, ideas or wishes being transferred from their original object to a more acceptable substitute. It is most often used to allay anxiety …

The book – or rather, e-book — that worked this strange magic for us is The Survival of Thomas Ford, about which we learnt from a Twitter link by its author, John A. A. Logan, to a detailed history of the manuscript’s long string of rejections that we would call staggeringly unbelievable and absurd if we did not know it to be an impeccably accurate record of the state of conventional publishing in 2012. We began to watch John’s tweet stream after we found ourselves on the same side in an online debate about copyright in the age of the net; among the not-terribly-popular lobbyists for paying artists and writers for work in the age of e-pirating.

Soon, we were reading arresting sentences and sequences like these:

Jimmy sipped Coke and watched Robert out of an eye’s sly edge.

…

Robert believed that it was sometimes possible for the universe to overlook certain misdeeds, even serious ones. He had believed from an early age that the universe made errors, usually errors of omission. He believed, in fact, that Jimmy’s very existence was evidence of such an error.

If Jimmy was a vacuum, then Robert had been sucked in.

We registered something indefinably Scottish in the observations, the styles of expression, and marvelled at the absence of the too-familiar props in mass-market thriller-writing – glamourising brand names and settings – and clichéd ‘middle-class’ attitudes to people on less fortunate social rungs, or the reverse. A hospital cleaner, finding herself for the first time in an urban garden thinks,

This garden was like a machine for escaping the city.

After weeks of reading in tiny sips, for a lack of time, we reached a scene in which a father punishes his adult son for mistreating immigrant Polish bricklayers by flinging him into the mud with a feral twist that all but breaks his neck. Soon, there are characters bleeding from kitchen knives stuck in their sides and … For fear of the spoiler effect, we’ll stop there and say that we usually go to extremes to avoid sustained violence in any form, and were able to endure no more than a half-hour of The Silence of the Lambs. But we could not stop reading Survival.

John Logan is certainly not trying to be Muriel Spark, the grand priestess of modern Scottish literature, but as real life trouble intensified and spun out of control for us, we grew increasingly impatient with audio recordings of still gritty but tired recent books by Ian Rankin to which we had turned – because they were sitting on our library re-shelving cart – to make sure that we stayed fully alert on long driving expeditions on featureless roads. We longed to listen instead to the fresher writing voice and inspiration of the next chapter of the Logan thriller with its endlessly surprising perspectives and frequently excellent prose.

That last attribute is something John’s work has in common with other young Scots writers, too many of them unpublished, or self-published and unnoticed because of hair-raisingly nonsensical sagas of rejection – like his. The extract from a modernist — Barthian, Bellowish, (William) Burroughsian – novel by Sean Murray in the epigraph for this post came from a discussion of misogyny in the work of male novelists on Donkeyshott and Xuitlacoche, the domain of a blogger, Philip Hall, who has a head crammed with stimulating, cosmopolitan ideas. The guest-post on his blog spotlighting the Adorata remarked, ‘If your life depended on it, could you imagine Mailer creating a female character with a thesaurus stored in her car?’

In disembodied cyberspace, post-Gutenberg has had more than one encounter with these Scottish scribes — whose energy and dauntlessness recall ‘O, young Lochinvar is come out of the west/Through all the wide Border his steed was the best …’. We have been honoured by bracing and uplifting encouragement from them – which might make our motives for writing this post suspect. Fear not. We have … ahem … credibility to protect, as obscure as we are, in this patch of the net.

Before we leave you to read a clip from John’s account of his well-deserved — but hard-won — success with publishing Survival as an e-book, we have a question. Can we — those of us who care about the absurdity of neither John nor Sean Murray finding a conventional publisher with conventional marketing muscle — do something to finance the efforts of writers suffering from the disappearance of editors capable of nurturing unpublished writers? Or sustaining the efforts of those who already have stellar publishing credits, but have run afoul of the salespeople promoted to über-gatekeepers at some of the most famous literary imprints?

We have made suggestions before, about how this might be done – using micropayments, something better than Kickstarter and a new way of organising publishing as a massively inclusive, subscriber-based ‘co-owned’ medium.

That post-Gutenberg — thousands of miles from Scotland, with no real-life acquaintance with any of these scarcely-known Scottish scribblers — should care so much about helping them find support surely means that something can be done, and soon.

Over, now, to John himself – although you will want to read his entire record of the death of common sense. The last page of Survival says that John has been published by Picador, Vintage and Chapman – all in the loftiest tier of the serious end of the book business.

… In December 2010, the literary agent phoned me for 90 minutes, to tell me he was sure a major publishing house’s editors had wanted to take my book, but then at the meeting with the sales dept the sales folk for this publishing house had said that I “reminded them of someone they had had high hopes for two years earlier but then had lost money on”. And that ended that house’s interest in the book.

A little later, the senior commissioning editor at another major UK publishing house wrote to say “I think John Logan is a hugely talented writer. I love books like this that have the pace and excitement of a thriller but the voice and emotional depth of a literary novel”. But again when it came right down to it, no sale!

Then my agent passed the book to a film consultant who worked with him. She told him my novel, The Survival of Thomas Ford, was the best book she had read in that literary agency in the last 4 years. This was taken very seriously, as this film consultant had discovered Slumdog Millionaire as an unpublished manuscript and was responsible for it getting developed into a film …