Cartoon by an unknown artist at an exhibition, King’s Cross, London, 24 March 2012

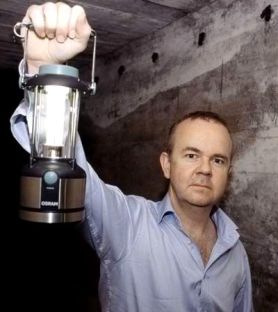

Photograph by Katy Stoddard

A journalist giving evidence at the Leveson Inquiry on 23 May answered questions from the lead counsel, Robert Jay, QC, about his written submission – until the Bench intervened:

Q. … Can I ask you … about the arrangements or the negotiations with politicians which you say can become very convoluted. …

A. … I do find it easier not to have politicians as personal friends. …

Q. In the context of the symbiotic relationship you go on to describe?

A. Yes. I mean, it is like ticks and sheep, isn’t it? One can’t exist without the other.

Q. … You might become parti pris or become just a little too understanding. It’s obviously those vices which you carefully eschew. Is that fair?

A. Yeah, I mean I don’t want to set myself up as some sort of absolute prig here. … I find it easier and cleaner to have a disconnection, that’s all … [A]nd the only justification, I think, for our existence, is that we act on behalf of the citizen. We don’t act on behalf of the powerful or the vested interest.

LORD JUSTICE LEVESON: Nobody will think you’re a prig, Mr Paxman, having just compared yourself to a tick.

In 1999, after Jerri FitzGerald – the only doctor in a 41-person team on a research expedition to the South Pole – discovered a lump in her breast, she ‘performed a biopsy on herself with the help of non-medical staff, who practised using needles on a raw chicken.’

Everyone expecting courageous, detached professionalism in another sphere from newspapers covering the Leveson Inquiry into press standards and practices has been sorely disappointed. The most important story emerging from the hearings – confirmation of judicial sanction for members of the public who choose to blog, and for an unprecedented range of sources of information for voters seeking to make good voting decisions – is being concealed through a nearly exclusive focus on the implications for David Cameron’s government of sensational revelations from the phone hacking scandal.

All reporting on the Leveson proceedings by the press has been highly selective. Readers have even been deprived of such fun as the judge’s gentle takedown of the BBC’s best-known inquisitor on politics – the suave and debonair TV journalist Jeremy Paxman – recorded in our epigraph.

Reporting by traditional media about the changed status of blogging is non-existent, scant or distorted – sometimes gravely. Andrew Marr, one of the most respected political commentators in Britain, had this exchange with the Inquiry’s chief interrogator, Robert Jay:

Q. … [A]n article from The Guardian, 11 October 2010, … reports you as dismissing bloggers as “inadequate, pimpled and single” and citizen journalism as “the spewings and rantings of very drunk people late at night”. … Is that comment about … the tone and quality of some of the online debate, or is it a more fundamental criticism of bloggers as being detrimental to the good name of journalism?

A. …[I]t’s partly a symptom of my deadly weakness for a vivid phrase. It was a comment really aimed at the enormous amount of anger and vituperation that seemed to me to be swilling around parts of the Internet, most of it anonymous. I was probably a bit out of date even if I was saying that. Now, you know, you look around and a lot of the most influential highly respected political commentators aren’t newspaper journalists, actually, they are bloggers.

In The Guardian, Dan Sabbagh supplied a master-class in biased reporting in a news story radically watering down Marr’s testimony about the value of political commentary by bloggers:

Lord Justice Leveson has queried whether bloggers would have to be brought in a revised system of press regulation, as he heard evidence from Andrew Marr about the growing power of political websites.

The BBC journalist and politics show presenter said that ConservativeHome and other sites are “now as influential as any newspaper” and any new system of regulation proposed by the judge “would have to include those alongside newspapers”.

Whereas the Sabbagh report had the judge merely reflecting ‘rhetorically’ on ‘the boundaries of regulation’ – meaning the degree to which bloggers would be treated as part of the 4th Estate – anyone paying close attention would have heard Lord Justice Leveson agonise about a ‘nightmarish’ task of a very different sort. What he said was clearly predicated on bloggers and citizen journalists not being be excluded from any new system of press regulation. His dilemma, he explained, lay in deciding exactly who should be required to redress complaints about journalistic misbehaviour in that new system – that is, wrongdoing not just by those traditionally considered journalists but by anyone practising journalism.

The judge must wrestle with the distinction within the blogosphere between those whose writing amounts to comments for the sake of commenting, versus ‘those that are in the course of — if you like, a trade or business.’ Or, as he later rephrased that division, bloggers and other newcomers who are ‘simply commenting and those who are doing more and getting towards the business end of journalism.’

It is money changing hands for commentary that is, for him, the key point of difference between traditional and non-traditional journalists – not levels of expertise, or indeed any intrinsic entitlement to comment.

In another fascinating interlude in that day’s testimony, Andrew Marr noted – earlier – that a special category of political blogger had appeared on the scene:

I think what the world of the influential political blogger has done is introduced a new player into the system who isn’t the full-time professional journalist with a press card working at Westminster under an editor and isn’t a politician, but is somewhere between the two. A lot of these people are card carrying party members. […] They have particularly strong contacts with their side. And therefore you can’t treat them as old-fashioned journalists under old-fashioned journalistic codes …

Then, with commendable honesty, he added that newspapers had begun to employ these professionally partisan political bloggers – if not mentioning what post-Gutenberg has in recent posts about the ‘old-fashioned’ press now claiming partisanship as a basic right of a free press. Paid political bloggers, he said, are

an influential new thing. I mean, even a lot of the papers are picking people up and using them as commentators now. I think the old distinction between a political player and would-be professional journalist is breaking down, and any system which is built upon the old system will quickly look out of date as well.

On Dan Sabbagh’s keyboard, that testimony was conspicuously tweaked, like the rest of his report – and made no mention of newspapers bringing spin-doctors into the fold:

Marr said that political bloggers were often “card-carrying party members” often with “strong contacts with their side”, which meant that they could not be treated as “old-fashioned journalists” but were nevertheless increasingly significant.

What a good thing it is that no member of the Inquiry’s outstanding legal team misses a beat.

There was, for instance, the moment when Marr told the presiding judge that the ‘buy-in from the editors and the journalists who are going to be part of it,’ would be critical to the success of any new system of regulation introduced.’ He emphasised that ‘you need them to be plugged in … enthusiastically and willingly so.’

This conversational minuet ensued:

LORD JUSTICE LEVESON: In relation to buy-in, of course, if I’m going to recommend any system, it has to be a system that everybody has to buy into.

A. Yes.

LORD JUSTICE LEVESON: It will only have a chance of working if it works for the press, it works for the public as well.

A. Mm.

… Not for ages has anything in public life offered the satisfaction of seeing right being done to remotely the same degree.