[ On 10 July 2012, The Independent, a ‘liberal’ London newspaper, declined to publish a comment on press reform linked to this post. That polite comment is here. ]

Niklaus Manuel’s ‘Dance of Death’ (‘Totentanz’, 1516-1519) was a hugely popular theme as Gutenberg presses proliferated and the Renaissance was in full sway. It could have symbolised a coming-to-terms not just with death but the dying of old ways.

Presiding over an Inquiry whose conclusions will shape the afterlife of the British press – doomed to extinction by digital media and the new voices of the 5th Estate – Lord Justice Leveson keeps reminding us of the contradiction in the difficult job he has been given. What mechanisms can he recommend to the government for the enforcement of ethical behaviour by the 4th Estate without ‘imperilling the freedom of expression or our free press’? – as he put it during Tony Blair’s testimony in late May.

Post-Gutenberg would like to recommend a fragment of ancient Chinese philosophy as a frame for thinking about a solution to his quandary. Lao Tse reportedly said, in the 6th century BCE,

If we wish to compress something, we must first let it fully expand.

Rule-making can be seen as a sort of compression – in the sense of limiting, constraining and controlling. It is too soon for anyone, even the admirably wise men at the summit of Britain’s judiciary today, to draft rules for media being turned inside-out by the digital revolution. As perspicacious witnesses have pointed out, any new regulations that minutely specify what the 4th Estate can and cannot do must inevitably pronounce on who should be considered a journalist. How can that be done when the profession’s boundaries are being obliterated by the arrival of the 5th Estate?

It would be disastrous if the Inquiry were to lead to any blocking or impeding of this successor to the 4th Estate. What the arrival of the 5th Estate means for the press is that it has to share the megaphone it has so far had all to itself. This succession is directly in line with the evolution and improvement of democracy – something that people everywhere want dearly, a yearning that events like the Arab Spring have dramatised.

To watch the Leveson hearings is to see the presiding judge agonise over too many details that an unimpeded 5th Estate will soon make irrelevant or outdated. They take up too much of his time, even when he understandably declines to deal with them in an Inquiry being criticised for taking on too much. As Dan Sabbagh noted in a good summing-up in The Guardian last week,

Leveson has so far showed little apparent desire to get into the question of the ownership structures of newspapers: when invited … to set a cross-media ownership limit that would force a Murdoch sale of the Sun or the Times, Leveson fought shy, “because that involves all sorts of competition issues which would require quite detailed analysis”.

Instead, Leveson went elsewhere to debate some practical solutions. The judge has been surprisingly consistent in the views he has espoused, taking the approach of testing out ideas periodically with witnesses he likes. Leveson is clearly sceptical of the PCC [Press Complaints Commission], telling Financial Times editor Lionel Barber in January that the body was not “really a regulator” but a “complaints mechanism” – and that it needed to be supplemented by another body, a new kind of court, “some sort of arbitral system” to cover libel and privacy claims – an imagined body that the judge said would be designed to be low cost – or to use a phrase he repeated many times “not make extra work for lawyers”. Its nearest analogue would be the industrial tribunals, or the arbitration system used in the construction industry.

Post-Gutenberg likes the way the judge is thinking about a replacement for the defunct and essentially toothless Press Complaints Commission. We would also be happy to see the criminalisation of a small set of completely unacceptable infractions, such as extraordinary invasions of privacy by phone hacking and other underhand means.

But instead of pointless brain-cudgelling about precisely what percentage of which communication medium newspaper conglomerates like Rupert Murdoch’s should be allowed to own, Lord Justice Leveson’s highest priority should be to open the way to the largest number of competitors for the 4th Estate.

In other words, expand, don’t compress should be the principle guiding his recommendations to the government in September.

Check bad behaviour on the part of today’s media elite by maximising opportunities for the outsiders of the 5th Estate to offer alternative presentations of facts and unfamiliar opinions, and to challenge and expose the biases and mistakes of every sort of media, new and old.

There is no shortage of good ideas for the democratic licensing of access to sensitive information by both professional and non-professional disseminators of facts. In a post a few months ago on the blog of the International Forum for Responsible Media (INFORRM), Hugh Tomlinson QC made an excellent suggestion about ‘benefits for public interest journalism of creating a category of “accredited journalists”’. These would be …

… a sub-category of those writing for publication [who] should be given specific privileges to assist them in their work. […] [P]rivileges should not be granted to journalists simply because they are employed to write or because they work for a media organisation. Neither should the privileges be granted to any “citizen journalist” who claims to be writing public interest stories. Rather, the privileges should be made available to those who pass through a gateway policed by a voluntary independent regulatory body and sign up to an enforceable code of responsibility. [post-G’s ital.]

There are new ways of organising and financing journalism that could use Lord Justice Leveson’s support – even if that only means he will be careful not to hobble the reorganisation of the media as, for instance, a set of cooperatives in which readers and viewers could be offered the chance to become co-owners. In recent months, proposals for setting up and running these have been increasingly detailed and specific. (See, for instance, the mention of Paul Smalera’s suggestions in ‘Why a keiretsu-cooperative is a gentle transition for old media …’.)

The mere existence of the Leveson Inquiry has already had salutary effects. To give a small but critical example, the moderation of comments in The Guardian’s popular comments sections has become far less trigger-happy. Commenters are not being censored quite so reflexively for opinions or factual posts that conflict with that newspaper’s views and political positions, or criticise its friends. Last weekend, it was heartening to see a post about the Inquiry itself opened for comments after months of prohibition on grounds that made no sense – and to be able to read contributions to the debate about Ian Jack’s illuminating comparison of Leveson with an earlier government investigation of press practices.

As for the Leveson hearings, per se, their radical transparency — with a presiding judge confident enough to muse aloud and react spontaneously to testimony — goes far beyond what many of us could even have imagined as a model of open government. (The best demonstration came an hour after this post: here). American lawyer friends looking on in awe tell us that nothing in the US system would permit Americans to copy the form of these proceedings.

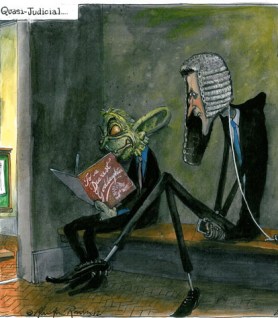

Most amazing has been the discovery that the conduct of the Inquiry is characteristic of an exceptionally progressive judiciary. Utterly unlike the notoriously slow-moving and stodgy legal system wickedly satirised in Dickens’s creation, Jarndyce and Jarndyce — a court case that grinds on for generations – Britain’s top judges are not just acknowledging the implications of new communications media and adjusting to them, but doing so faster than the professionally nimble 4th Estate.

Post-Gutenberg only recently came across a news report from the spring of last year about a speech in Israel by the Lord Chief Justice, Baron Igor Judge, who put Sir Brian Leveson in charge of this indescribably gratifying investigation into press culture and practices. He explained that in Malta, where he was born, one of his grandfathers owned and edited a tiny newspaper. His sympathy for the press’s problems is, in a sense, inbred. But he favours the transparency and inclusion that are more the defining characteristics of the 5th than the 4th Estate – even for keeping his own legal system honest:

His “fervent hope” was that new technology would make it easier for the media to be “present” in court, reporting the proceedings, and “the present trend of fewer and fewer reporters in every court would come to an end”.

In an apparent reference to “virtual” courts based on video-conferencing, Judge insisted that justice should be done “in a public forum to which the public, or the media, has access”.

He continued: “Technology must not lead to justice done in secret, or some form of hole-in-the-corner justice.“

Post-Gutenberg wishes to offer just more one scrap of advice to Lord Justice Leveson – who has invited everyone, however obscure, to contribute thoughts to his hearings: please do not allow political partisanship by the press to be conflated with press freedom. As we observed in a recent post in this spot, sanctioning political one-sidedness means licensing powerful media owners to be king-makers, with all the compromising wheeling and dealing that goes with that. It means condoning the skewed reporting of the facts so essential to the functioning of a genuinely democratic government.

With a fully licensed 5th Estate in full cry, media conglomerates trying to run Britain, with lots of help from British prime ministers – or what the Economist appears to dismiss nonchalantly as the inevitable ‘proprietor problem’ — should be shown their proper place. And where would that be? If not oblivion, then as far below the salt as possible.